Whispers in the Ledgers: The Final Days of Britain's Slave Empire

The Ink Had Not Yet Dried

It is easy, now, to speak of abolition as a triumph —

a moral awakening, a righteous pivot from savagery to civility.

But history does not turn so cleanly.

Not when the ledgers still reek of blood.

Not when the archives still whisper.

Between the years 1806 and 1808, the African Company of Merchants —

an official arm of British power in West Africa —

sat trembling on the edge of history.

And in the pages of their records, locked away under Reference T 70 in the UK’s National Archives,

we can hear the ghost of empire learning what it cannot unlearn:

That the trade in flesh was ending.

And no amount of profit could stop it.

A Business of Bones

For decades, the African Company of Merchants was the British Empire's outstretched hand along the West African coast —

a company built not on goods, but on people.

Men, women, and children were its currency.

Its forts — Cape Coast Castle, Fort William, Fort James —

were not trading posts, but holding pens.

Its officers were not just merchants — they were engineers of human misery.

The T 70 archives do not scream.

They do not weep.

But they record, with cold clarity, what screaming and weeping look like on paper.

Receipts.

Manifests.

Ship names.

A price per head.

Notes on chain lengths.

Cargo lists: 350 souls, male, aged 12–40.

“Losses at sea: 17.”

The handwriting is neat. The grammar precise.

It had to be. Parliament would read these letters.

So would investors.

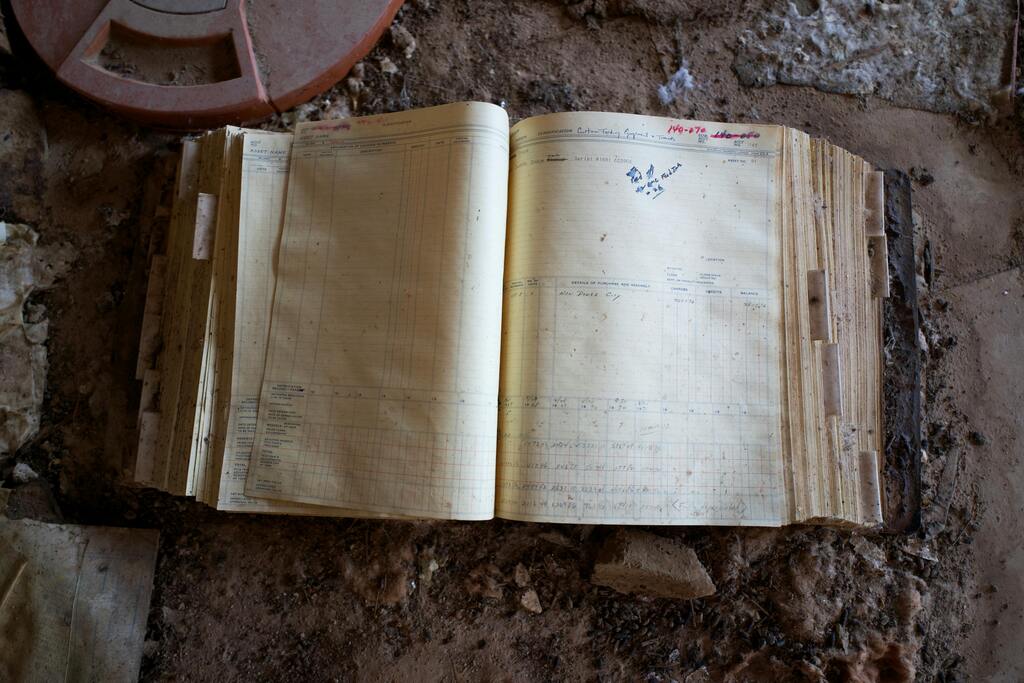

Old ledger

The Tide Turns

Then came 1807 —

and with it, the Slave Trade Act.

The Parliament that had once funded the trade now turned its pen against it.

The sale and transport of enslaved Africans by British subjects was declared illegal.

Not slavery itself — not yet —

but the machinery that fueled it was to be dismantled.

And so, inside the offices of the African Company of Merchants,

something more terrifying than rebellion, or disease, or market loss occurred:

Uncertainty.

A Company in Freefall

In the meeting minutes of 1806–1808, the tone begins to shift.

There are letters of concern from coastal forts,

pleading for guidance:

“If we can no longer sell the captives, what are we to do with them?”

There are calculations of lost revenue.

Ship captains delaying voyages until the final hour before abolition,

rushing to sell human cargo before the deadline struck.

There are strategies to pivot:

Suddenly, the company seeks to trade in palm oil, ivory, gold, dyewood, spices.

“Legitimate commerce,” they call it —

a word that falls bitterly flat when read alongside

wage rosters showing dockworkers still handling shackled men in January 1808.

One letter, dated weeks after the act took effect,

requests guidance on dealing with a slave cargo stranded off the coast of Anomabu.

The writer asks, almost apologetically, whether these captives could still be sold “quietly.”

Cape Coast Castle, Ghana, West Africa (c) Remo Kurka

The Forts: Ghosts in Stone

In the pages of these archives, you see it all:

The cost of candles burned at Fort James.

The repair of a cannon at Cape Coast Castle.

The provision lists: rum, biscuits, rope... manacles.

Even after the trade was banned, these forts remained —

symbols of a past the Empire struggled to abandon.

They tried to cleanse them.

Rebrand them.

But stone remembers.

Today, tourists walk through those corridors,

posing for photographs under crumbling arches.

They hear echoes, perhaps —

but the ledgers hold the truth.

Correspondence with London: A Nervous Empire

The company's letters to the British Parliament — now carefully preserved —

read like dispatches from a crumbling outpost.

They plead for new grants.

They warn of revolts.

They insist on loyalty to the Crown.

But underneath it all is panic.

They know.

The game has changed.

And no empire — no matter how vast — can build a future on a foundation of shackles forever.

The Legacy of T 70

Today, the T 70 records sit in climate-controlled vaults, bound and categorized.

Historians comb through them to understand policy, trade, imperial reach.

But to read these documents is not merely to study the past.

It is to listen.

To the creak of ships that no longer sail.

To the clash of chains that should never have been forged.

To the ink-drawn architecture of a crime that spanned continents and centuries.

These were not just business records.

They are the autopsy reports of empire.

Final Thoughts

The African Company of Merchants did not collapse overnight.

But between 1806 and 1808, it began to rot from within.

The world was changing.

And for a company built on selling bodies,

no pivot to ivory or palm oil could cleanse the stench of what had come before.

They tried to forget.

But we remember.

And the archives do not lie.

PODCAST: Echoes of the Coast: Forgotten Voices of the Gold Coast

🎧 EPISODE: The Walls of Fort William – A Fante Woman’s Story 1806

Want to Know More?

You can access these historical records at the UK National Archives, under Reference T 70, which houses the African Company of Merchants' ledgers, correspondence, and reports from the era.

Below are 2 PDF links:

- Here, as an example, you van read a PDF about Liverpool and Slave Trade

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Foundation ofthe Kingdom of Galinhas in Southern Sierra Leone,1790–1820 (PDF)

Explore them — but know this:

Once you read the names, the numbers, the notes…

you will never un-hear the whispers in the ledgers.

Other related websites:

#Abolition1807 #SlaveTradeArchives #BritishEmpire #T70Files #BlackHistoryUnfiltered #EchoesOfTheCoast

Article by (c) Remo Kurka 2025

Other websites - Not shown within our main site-map:

- Fort Teshie (Fort Augustaborg) - Teshie, Accra)

- Fort Komenda - 2 Forts at Komenda (Central Region, near Elmina and Cape Coast, Central Region)

- Forth Conraadsborg (Elmina, Central Region)

- Fort Ussher (Accra, Ussher Town)

- Fort Wiliam (Cape Coast, Central Region)

- Fort Victoria (Cape Coast, Central Region)

- Fort Batenstein (Butree, Western Region)

- Fort Patience (Central Region)

- Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park and Museum (Accra)

- Yaa Asantewaah Museum (Ashanti Region)

- The W .E. B. Du Bois Centre for Pan African Culture (Accra)

- Volta Regional Museum, Ho (Volta Region)

- Kakum National Park (Central Region, near Cape Coast)

- Aburi & Aburi Botanical Gardens (Aburi, Eastern region)

- Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum Nkroful (Western Region, Nkroful)

- Official website of Tetthe Quarshie Art market (Accra)

🇬🇭 Ghana3d.com Gateway Experience 360

Find your roots and rise — Ghana3d.com Gateway Experience 360 is your ultimate guide to cultural, historic, and soul-stirring adventures. Whether you're returning to your ancestral land or exploring Ghana for the first time, we offer curated journeys that connect you deeply to the spirit of West Africa. From powerful walks through Cape Coast & Elmina slave castles to the vibrant rhythms of Accra’s nightlife. From sacred village ceremonies to awe-inspiring natural beauty — your journey starts here.

- ✔ Instant Confirmation

- ✔ Free Cancellation

-

✔ Best Price Guarantee

You'll receive a full refund if you cancel at least 24 hours in advance of most experiences.

3 girls selling fruits and food at the road side. (c) Strictly by Remo Kurka (photography)